Inspired by Suh Young Choi.

In this section, we will be simulating different types of vision deficiencies: color blindness (color vision deficiency) and blurred vision (such as near-sightedness or far-sightedness). In the United States, color blindness affects about 1 in 12 men and about 1 in 200 women while blurred vision affects about 1 in 3 people. We can help design more accessible visualizations by simulating different kinds of vision deficiencies using computer vision techniques.

import imageio.v3 as iio

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

plot = iio.imread("plot.png", mode="RGB")

def compare(*images):

"""Display one or more images side by side."""

_, axs = plt.subplots(1, len(images), figsize=(15, 6))

for ax, image in zip(axs, images):

ax.imshow(image, cmap="gray")

ax.set_axis_off()

plt.show()Simulating Monochromatism¶

Monochromatism (also called achromatopsia) is the rarest form of color vision deficiency, in which an individual has total color blindness. In other words, they see everything in grayscale.

Write a function grayscale that takes an RGB image and returns a new, single-channel grayscale image with the weighted average of the color channels:

Multiply every value in the red channel by 0.3

Multiply every value in the green channel by 0.586

Multiply every value in the blue channel by 0.114

Add the new red, green, and blue color values for each pixel in the image as a single-channel, grayscale image.

def grayscale(image):

r, g, b = image[:, :, 0], image[:, :, 1], image[:, :, 2]

result = ...

return result.clip(0, 255).astype("uint8")

compare(plot, grayscale(plot))Simulating Protanopia¶

Protanopia (pro-tuh-NOPE-ee-uh), also known as red-blindness, is a form of color vision deficiency for red light. A person with protanopia has cones that are less sensitive to red light.

Write a function protanopia that takes an RGB image and returns a new image with color values weighted according to the formula:

np.stack can be used to recombine separated RGB color channels back into a image with the argument axis=-1 to “stack” the channels along a new, last dimension.

np.stack([r, g, b], axis=-1)def protanopia(image):

"""Adjusts the color values of an image to simulate protanopia"""

r, g, b = image[:, :, 0], image[:, :, 1], image[:, :, 2]

return np.stack([

...,

...,

...,

], axis=-1).clip(0, 255).astype("uint8")

compare(plot, protanopia(plot))Simulating Deuteranopia¶

Another type of color vision deficiency is called deuteranopia (doo-ter-uh-NOPE-ee-uh), or green-blindness. A person with deuteranopia has cones that are less sensitive to green light. Deuteranopia and protanopia are often grouped together under the umbrella term of red-green blindness, since people with either color vision deficiency have difficulty differentiating red and green values. The simulation for deuteranopia will appear very similar to the simulation for protanopia.

To simulate deuteranopia, write a function reweight that takes an image as well as 3 lists of weights for RGB values and returns a new image with color values reweighted accordingly. The deuteranopia function then calls reweight with the RGB weights for simulating deuteranopia.

def reweight(image, r_new, g_new, b_new):

return np.stack([

...,

...,

...,

], axis=-1).clip(0, 255).astype("uint8")

def deuteranopia(image):

return reweight(

image,

[ 0.36, 0.86, -0.22],

[ 0.28, 0.67, 0.05],

[-0.01, 0.04, 0.97],

)

compare(plot, deuteranopia(plot))

compare(protanopia(plot), deuteranopia(plot))Simulating Tritanopia¶

The final type of color vision deficiency we’ll simulate is tritanopia (try-tuh-NOPE-ee-uh), or blue-blindness. A person with tritanopia has cones that are less sensitive to blue light. The simulation for tritanopia will appear quite different from the simulations for deuteranopia and protanopia.

Write a function tritanopia that takes an RGB image and returns a new image with color values weighted according to the formula:

Call the reweight function in your implementation.

def tritanopia(image):

return ...

compare(plot, tritanopia(plot))Simulating Blurred Vision¶

In lecture, we learned how to apply convolution to blur a grayscale image. Let’s learn how to use convolutions to blur RGB images.

Write a function box_blur that takes an RGB image and a kernel size and returns the result of applying the specified amount of box blur to the image. The provided convolution code works for grayscale images, but doesn’t work for RGB images due to broadcasting errors. Fix the broadcasting error.

def box_blur(image, kernel_size):

# Prepare result shape

image_height, image_width, image_channels = image.shape

result = np.zeros((image_height - kernel_size + 1, image_width - kernel_size + 1, image_channels))

result_height, result_width, result_channels = result.shape

# Setup the box blur kernel as a 2-dimensional square array

kernel = np.array([1 / (kernel_size ** 2)] * (kernel_size ** 2)).reshape((kernel_size, kernel_size))

display(kernel.round(3))

# Apply the kernel via convolution to every subimage

for i in range(result_height):

for j in range(result_width):

subimage = image[i:i + kernel_size, j:j + kernel_size]

result[i, j] = np.sum(subimage * kernel)

return result.clip(0, 255).astype("uint8")

compare(plot, box_blur(plot, 9)) # Try changing the kernel sizeAnother way to simulate blurred vision is gaussian blur, which uses a gaussian kernel.

First, apply your broadcasting fix by copying your code from the previous box_blur function over to the gaussian_blur function.

Then, write a function gaussian_kernel that takes two parameters n and sigma and returns the n-by-n gaussian blur kernel, where each element is defined as:

Call np.exp(...) for . When implementing , use floor division by writing // instead of / to ensure the resulting kernel will be symmetric.

def gaussian_kernel(n, sigma):

kernel = np.zeros((n, n))

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

kernel[i, j] = ...

return kernel / np.sum(kernel)

def gaussian_blur(image, kernel_size, smoothing_factor):

# Prepare result shape

image_height, image_width, image_channels = image.shape

result = np.zeros((image_height - kernel_size + 1, image_width - kernel_size + 1, image_channels))

result_height, result_width, result_channels = result.shape

# Setup the box blur kernel as a 2-dimensional square array

kernel = gaussian_kernel(kernel_size, smoothing_factor)

display(kernel.round(3))

# Apply the kernel via convolution to every subimage

for i in range(result_height):

for j in range(result_width):

subimage = image[i:i + kernel_size, j:j + kernel_size]

result[i, j] = np.sum(subimage * kernel)

return result.clip(0, 255).astype("uint8")

compare(plot, gaussian_blur(plot, 9, 1)) # Try changing the kernel size and smoothing factorMaking visualizations accessible to screen readers¶

Beyond simulating color blindness and blurred vision, millions of Americans use screen readers: apps that read the contents of a computer screen aloud (using a generated voice) or Braille. However, visualizations are often inaccessible to screen readers. This is especially the case for visualizations represented as images, but UW researchers have studied how interactive visualizations can be made more accessible as part of the VoxLens project.

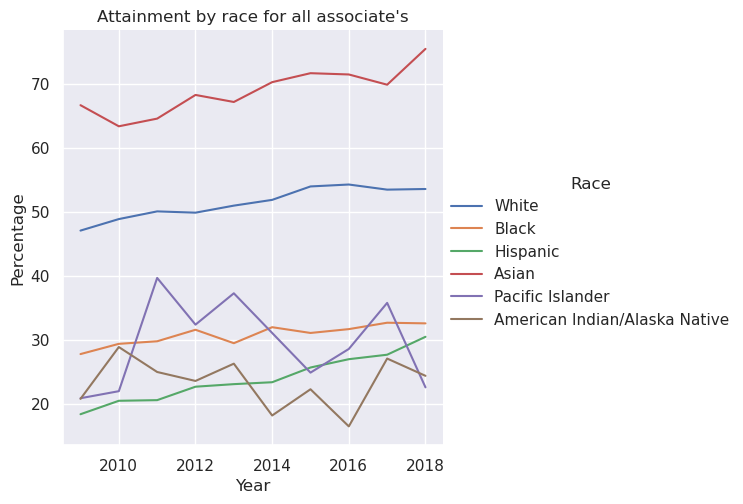

For visualizations represented as images, adding alternative text (alt text) is one way to help screen readers understand the purpose and information communicated by a visualization. A longer description should typically be made available in the surrounding text as well to give context to the image for all readers. Amy Cesal provides guidance on Writing Alt Text for Data Visualization.

In Markdown cells, alt text can be included when embedding an image by writing text within the square brackets:

Edit the following cell to add a descriptive alt text in the format, “Chart type of type of data where reason for including chart” (replacing bolded text appropriately).